Will putting the Draft Labour Code on the backburner increase the burden on employers?

26 Jan 2018

A seemingly trivial but quite important piece of information came to the fore on 27th November 2017. The Maharashtra Government fearing backlash shelved the bill of labour reform that otherwise would have eased the burden of 37 234 factories reeling under unviable losses. Politicisation of labour issues is the crucial factor for denigrating the status of manufacturing and its productivity in different states.

Indian labour market’s current state

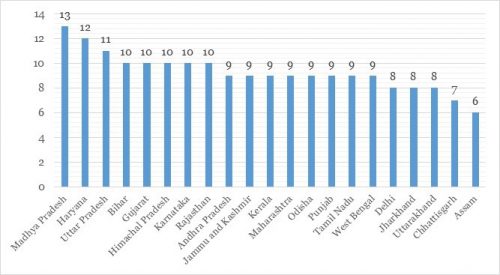

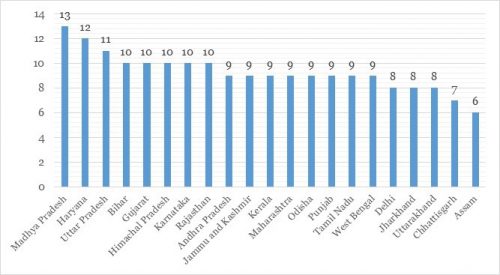

There are close to 45 labour laws for only 7 percent (NSS 68th Round) of the organised sector workers in India. The labour laws in India makes a distinction between people who work in “organised” and people working in “unorganised” sectors. This received a major update in the Industrial Disputes Act of 1947 that mandate almost all aspects of the employer-employee interface. There are 15 major laws that are important in terms of settling industrial disputes compensation of wages and so on. The figure below shows the number of labour laws in a state. Madhya Pradesh has the highest number of labour laws as per the above list while Assam has only 6.

Figure 1: Number of labour laws in operation among major states

Source: Author’s compilation from State Government web sources

Complexity and inconsistencies among labour laws are cited as a key deterrent to job creation in the formal sector. Of the country’s 473 million workers as of 2011-12 over 90 percent are informal workers without recourse to social security benefits such as pension medical care or other facilities. Many of these laws are outmoded and confusion prevails over several issues. Moreover if the size of a factory grows it increasingly becomes subject to constraining legislation that adversely impacted the level of productivity.

Mandatory registration for all workers

It is in this context that the Ministry of Labour and Employment introduced the draft Labour Code (March 2017) on Social Security and Welfare to regulate conditions for retirement health disability and other forms of security for all the workers including those in the unorganised sector. The proposed code subsumed 15 of the existing labour laws to promote universalisation of social security and extends to the entire workforce earning any income in cash or kind above the minimum wage. The regulation for registration of workers stipulates that if a worker is working in multiple entities then s/he must choose the employer through which s/he wants to register and all other employers would need to be informed. No entity including households can employ an unregistered worker and must register the worker within a specified time. Therefore compliance with the code would be an enormous challenge for employers to maintain records of the daily payouts to different workers over a period of time.

As per the code employers and entities employing more than the threshold number of workers must also register themselves. The definition of ‘entities’ includes households employing workers. However registering each household that employs domestic workers may turn out to be difficult while ensuring that they adhere to the norms of the code.

Contribution to the social security fund

Moreover the code mandates that each worker and entity contribute towards the social security fund to be set up by the state governments. The maximum limit for contributions by employers is 17.5 percent of the wages. In the formal sector workers would need to pay 12.5 percent of the wage or monthly income while the same proportion equally applies to the workers from the unorganised sector. For the owner-cum-worker category the person needs to pay 17.5 percent in his capacity as an owner and 12.5 percent as a worker. Thus a master craftsman operating from home may have to set aside 30 percent of income towards social security which is a substantial proportion and difficult in terms of its implementation. The disposable income of workers earning slightly more than the minimum wage would drop significantly if the payment social security contribution is strictly adhered to. Extending this compulsion for informal sector workers with uncertain and irregular incomes might prove to be an intolerable burden for them. However the state government at its own discretion can waive such contributions for a maximum of five years for some of the identified workers. It also offers for welfare funds to be set up for specific classes of workers for which the central or state governments could make contributions. The code also empowers the state governments to pay contributions on behalf of specific workers or refund contributions made by employers.

Policy interventions to ensure smooth implementation

The labour market institutions in India need to move to a flexible set-up for the employers in employment decisions to build competitiveness in an aggressive global arena. A strong social security system could offer protection to workers for temporary unemployment periods. The code does not appear to have this provision. A universal social security system for workers is a laudable initiative but the government would need to provide this through its own contributions for poorer workers. In this count the role of the MNREGA may need to be redesigned to provide benefits for all workers including unemployment medical insurance or retirement benefits.

The universal coverage of obligatory registrations and contributions would need to be non-restrictive and synchronised for poorer workers so that the country can move towards higher job generation with adequate social security. On earlier occasions well-intentioned legislation (like the Land Acquisition Act) could not create a desirable impact due to their applicability on the ground. The draft social security code is going to be one of the most credible initiatives by the government but the real challenge lies in its execution and compliance.

By Saurabh Bandyopadhyay

Published in: Qrius, January 26, 2018